In most apocalyptic texts, sacrifice and redemption are idealistically portrayed together; A singular hero selflessly sacrificing something, otherwise beneficial to oneself, for the greater good. Realistically, sacrifice is not always good natured and seldom leads to redemption. This simplistic telescoped representation of sacrifice is merely an optimistic ideal in which misleads naïve audiences. The computer game, We Happy Few (WHF),1 is a unique apocalyptic text which deviates from the popular optimistic representation of sacrifice. WHF opens with an ominous vibe, repeatedly depicting characters carelessly sacrificing but not reaping any benefits, seemingly suggesting that sacrifices conventionally lead to negative outcomes. Using such a pessimistic portrayal of sacrifice, WHF interestingly amplifies players’ fear of being unable to atone for one’s sins instead of appeasing them. How is this fear further emphasised and what is the purpose of doing so? By examining the game plot of WHF, this article seeks to answer these questions and argue that there is a dangerous over-glorification of sacrifice and redemption, in which WHF seeks to provide a more comprehensive and thereby realistic overview of what sacrifice can lead to, reminding players of the implications of making careless sacrifices.

Before discussing WHF’s unique representation, there must be context on what the popular representation of sacrifice is in majority of apocalyptic texts and the reason behind the over-glorification of such representation. An example I would like to cite as a popular representation of sacrifice is the film Schindler’s List.2 Schindler’s List acts as a good comparison namely because it depicts the same temporal period WHF is depicting, World War II. As such, one would expect the two texts to share similar sentiments and portrayals especially since the general background is a historical event cast in iron. However, Schindler’s List has heavy emphasis on the Nazi character, Schindler, and how he redeems himself by sacrificing his resources, wealth and safety to protect as many Jews as he could from the merciless Nazis. WHF on the other hand barely portrays any sort of sacrifice leading to redemption. This ideal was only subtly hinted when the main character leaves the comfort of his city in the closing scene to face the painful truth and atone for his sins. Otherwise, a large chunk of the plot revolves around the portrayal of game characters and how they make self-centred sacrifices which lead to ignorance instead. From this comparison, it is evident that there is a stark contrast between the popular representation of sacrifice as compared to that of in WHF. Popular representations usually only take into consideration the possibility of redemption through selfless sacrifice while WHF accounts for multiple possible routes including ignorance. However, if popular representations of sacrifice in majority of apocalyptic texts portray such a jaded and oversimplified view, why are such texts so… popular?

Audiences are not sympathising with the popular representation of sacrifice, but instead sympathising with the history of the representation of sacrifice. Almost always do people associate the theme of sacrifice and its relation to redemption with the Bible.3 The Bible constantly highlights such a theme, acting as a ray of hope to dire situations. It implants in its readers the possibility of atoning for one’s sins and earning forgiveness from peers and God through selfless actions of sacrifice. The theme provides audiences with comfort that wrongdoings can be covered and eventually undone. While the positive theme may have been aimed at bringing hope to its readers, apocalyptic texts seem to follow this theme not out of the same intention, but rather as a product of human’s innate nature to imitate ideas according to the Girardian Mimetic theory, which states that humans have a strong tendency to reproduce already presented ideas.4 Especially since the Bible is a popular text in modern society, it is no wonder that the Bible’s theme of sacrifice and redemption was so easily recognised and adapted. Hence, apocalyptic texts’ popular representation of sacrifice is merely a blind transposition of the Bible’s representation.

While it is good to spark hope in viewers, it is dangerous when overdone. Over-glorification of the stereotypical representation of sacrifice and redemption can embed fictitious and unrealistically idealistic thoughts in the heads of audiences “through perpetual myth making”,5 making them less cautious of their actions. By being less cautious, audiences stop weighing the boons and banes of their actions, leading to mistakes which could have been avoided. Furthermore, when these audiences realise that they are unable to atone for their mistakes as easily as portrayed in majority of apocalyptic texts, they will feel hopeless. Thus, such over-glorification dilutes the positive theme intended in the Bible, turning it into one of false hope in which “is particularly dangerous; it has enormous power to seduce us – but it is a harmful illusion(,) it… captivates our thoughts, but does not deliver as promised”.6 What makes it more dangerous is the contagious power of texts in influencing majority of public opinions in popular culture. Due to technological advancements, texts can be shared globally with just a click of a button. The efficiency of such texts makes dangerous ideas propagate like a plague, influencing public opinions of mass audiences in a short period of time.

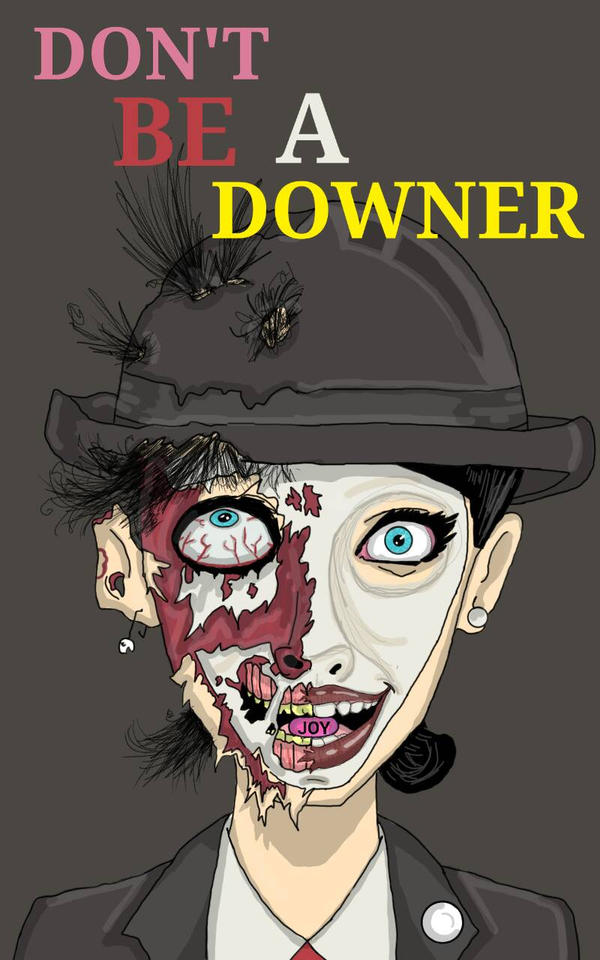

WHF is set in a 1960s drug-fuelled retro futuristic world. Acting as an alternative version of events during World War II, WHF portrays a dystopian English society (Wellington Wells) ravaged by war.7 In this alternative version, largescale chemical-warfare between the German empire and allies of Europe took place in Wellington Wells, damaging architectures and rendering most food inedible. In the war-torn state the city is in, its inhabitants became desperate and did something terrible. The producers of the game did not explicitly state what that was, but the inhabitants of Wellington Wells undeniably felt guilty for this terrible act. This guilt has driven them to consume a hallucinogenic drug, Joy, to create an eternal world of false happiness. However, the dependence on Joy has led to cultural changes and differences, resulting in the inhabitants becoming divided. Due to this division, the inhabitants deal with guilt through different forms of sacrifice which ultimately leads to their own demise. These inhabitants can be segregated into three groups: Wellies, Downers and Wastreals. To make players witness and comprehend the routes sacrifice can take, WHF forces players to engage in mandatory quests, causing players to explore the map and interact with game characters of each group on a personal level. Thus, this article will mainly be examining such mandatory quests to identify the unusual yet relatable representation of sacrifice WHF portrays, in which resonates with players and reminds them of the true nature of sacrifice.

In WHF, the Wellies are the embodiment of sacrifice leading to ignorance resulting from a lack of true belief (ignorance stemming from rejecting a known truth).8 They are the epitome of the perfect law-abiding citizen. This law would be to consume Joy.

As it is a personal choice of the individual to consume Joy, it is evident that the Wellies are fully aware of the sins they have committed but choose to reject this truth. In a bid to upkeep their delusion, the Wellies sacrifice memories, morals and individuality, clouding their view of reality with ignorance. It is interesting to note that the goal of sacrifice presented here is for personal gain and not for the betterment of someone else’s life as in popular representations of sacrifice. In the opening scene, the main character is seen censoring some articles in the news archive. Articles which are joyful are kept while articles which may invoke sadness are censored and permanently removed. Furthermore, an effect of Joy is to remove all negative memories. This physical-mental mechanism of erasing sorrowful memories highlights the strong desire of the Wellies to reject the truth and maintain their false happiness, causing them to be ignorant of their past mistakes.

As part of the game plot, players are tasked to help a character, Benedick Keyes, obtain flowers. The storyline goes that Keyes is trying to pursue a lady. Being a chemist, he decides to do so by creating a cologne which smells like that of a doctor, reasoning that all women are attracted to doctors. He soon realises that it is an utter failure in which the player will step in to resolve the issue by suggesting to Keyes to give flowers. This scene alone underscores the sacrifice of morals (Keyes intending to deceive the lady into a relationship out of falsehood) and of individuality (Keyes pretending to be “the typical man women are attracted to”). Sacrifice of individuality is further emphasised by how all Wellies perpetually wear white masks with a smile drawn on it, concealing both identity and emotions.

While the Wellies have sacrificed so much to maintain “peace” and “happiness”, they have made no progress in atoning for their sins. In fact, the Wellies are in a state of ignorance rather than redemption. This ignorance was intentionally self-invoked as a result of sacrificing to avoid the negative truth. The Wellies do not seem to want to redeem themselves possibly because they are either too ashamed or they simply do not care for the people they have wronged as much as they care for their own emotional wellbeing. What makes this so relatable is how humans are biologically engineered to be selfish for self-preservation9 and would normally build up psychological barriers to fend out negative emotions than to deal with it and overcome it truthfully.10 Players relate to this representation on an emotional level, reinforcing the less glamorous path sacrifice can and usually take due to their innate behaviour.

As the Downers and Wastreals are largely similar and make the same sacrifice, I will talk about them as a singular group, D&W. D&W are the manifestation of sacrifice leading to ignorance due to a lack of knowledge (ignorance stemming from insufficient knowledge).11 D&W are people who either refuse to take Joy or experience no effects from consuming Joy. While exploring the areas inhabited by D&W, players realise that most food and bandages he/she will find are rotten and dirty. As such, in order to survive, players will be forced to use such items throughout the game.

By creating the game plot as such, players are incessantly reminded of the sacrifice of usability of items. This constant reinforcement causes the focus of D&W to be largely on sacrifice rather than the outcome of it. This shifts players’ attention away from the supposed triumphant benefits of sacrifice, instead highlighting the tedious and less glorious journey of it which requires a lot of compromise, disincentivising players from making careless sacrifices. In an encounter with a game character, Johnny Bolton, the obvious insanity that guilt has driven these people to can be seen. Bolton appears jittery and engages in conversations with his stuffed toys, treating them as alive. This encounter is a display of the sacrifice of sanity in D&W. Since emotions are difficult to comprehend, WHF conveys the sacrifice of sanity through a personal encounter with a game character on top of the conspicuous displays of insanity through the daily actions of D&W, such as the constant bickering and rude remarks players receive when passing by them.

These sacrifices are made due to the D&W focusing too much of their attention on trying to make sense of the guilt, thus it can be said that D&W sacrificed out of kind intentions. Unlike the Wellies, D&W are always fully aware of the reality they are in since they do not succumb to the hallucinogenic effects of Joy. As such, they are not bubbled up in false happiness and have no choice but to acknowledge that they have done something wrong and that they need to redeem themselves. However, just like in real life, there is no clear-cut way to redeem oneself, thus D&W have no idea how to turn the situation around. They end up trying to comprehend the guilt and ponder on how to atone for their sins to the point they neglect their own emotional and physical wellbeing. While they have good intentions, they are not able to be the heroic figure majority of apocalyptic texts would normally portray. They end up being ignorant of the deterioration they have put themselves in. This group serves as a reminder that not always are players able to make up for their wrongdoings and that they must carefully consider the consequences of their actions lest they end up in a state of self-destruction. In more relatable real-life scenarios, WHF reminds players that even good intentions can lead to negative outcomes.12

Zooming out to a larger picture, WHF’s portrayal of sacrifice and ignorance can be applied to apocalyptic texts. Most apocalyptic texts convey hopeful messages by transposing the Bible’s representation of sacrifice and redemption. Joy can be juxtaposed with the popular representation of sacrifice in apocalyptic texts; where even though such positive messages uplift the spirits of players who may be facing difficult times, it compromises the negative portrayal of sacrifice which would otherwise act as a healthy balance. Consequently, audiences would take away with them a jaded view of sacrifice and false hope that they could one day become one of the heroic figures portrayed as long as they carry out some form of sacrifice. In other words, audiences end up in a state of false happiness like how the Wellies were in WHF. Ironically, WHF acts as a redeeming medium for apocalyptic texts, providing the needed negative balance to the portrayal of sacrifice, reminding players that sacrifice can in fact lead to multiple unsatisfactory paths apart from redemption. By setting WHF as a game, the intended message of the routes sacrifice can take is effectively conveyed to the players, reminding them the reality of sacrifice through its interactive experience and immersive plot.13 WHF provides a fictional plot with relations to real life, sending across an intuitive message that does not require in-depth knowledge of the player’s personal life to invoke an understanding of the true nature of sacrifice.14 At the end of it all, WHF can be seen as the effects of not consuming Joy, acting as the catalyst to realising true sacrifice and possibly redemption.

References

- We Happy Few, Steam, directed by Guillaume Provost, (2009; Montreal: Compulsion Games, 2016).

- Schindler’s List, DVD, directed by Steven Spielberg (1981; California: Amblin Entertainment, 1993).

- Clifford, Richard (English bishop), and Khaled Anatolios, “Christian Salvation: Biblical and Theological Perspectives.”, Theological Studies 66, no. 4 (2005).

- Daly, Robert J., “Phenomenology of Redemption? Or Theory of Sanctification?”, Theological Studies 74, no. 2 (2013).

- Alkmini Gkritzali, Joseph Lampel and Caroline Wiertz, “Blame it on Hollywood: The Influence of Films on Paris as Product Location”, Journal of Business Research 69, no. 7 (2016).

- R., Synder, The psychology of hope: You can get there from here., New York: Free Press (1994).

- “About We Happy Few”, Wehappyfewgame, Accessed 30 March, 2018, from http://www.wehappyfewgame.com/#about

- Pierre Le Morvan and Rik Peels, “The Nature of Ignorance: Two Views.” In The Epistemic Dimensions of Ignorance, ed. Rik Peels and Martijn Blaauw, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 25-31.

- Machan, Tibor R., “The Ethics of Benign Selfishness.”, Contemporary Readings in Law and Social Justice 5, no. 2 (2013).

- Halperin, Eran, “Emotional Barriers to Peace: Emotions and Public Opinion of Jewish Israelis About the Peace Process in the Middle East.”, Peace & Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 17, no. 1 (2011).

- Pierre Le Morvan and Rik Peels, (2016), 15-25.

- Levy, Santiago, Good Intentions, Bad Outcomes: Social Policy Informality, and Economic Growth in Mexico., Washington: Brooking Institution Press (2008).

- Ute Ritterfield, Michael Cody and Peter Vorderer, Serious Games: Mechanisms and Effects, (New York: Routledge, 2009).

- Muhammad Babar Suleman, “Like Life Itself: Blurring the Distinction between Fiction and Reality in the Four Broken Hearts transmedia storyworld,” Journal of Media Practice 15, no. 3 (2014).

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.