Pointing Fingers at the Grain: An Examination of Human Responsibility in “The Entire History of You”

by Sharlene Lim

In “The Entire History of You” (“TEHOY”) in British science fiction television series Black Mirror, the problem of the fallible human memory is addressed by writer Jesse Armstrong’s imagination of a kind of transhuman technology that aids humans in their day-to-day lives, which comes in the form of a “grain”, which is a small device implanted behind the user’s ear that records every sight and sound that its user experiences. Set in a society that has seen the proliferation of the grain, the episode follows the lives of a married couple, Liam and Ffion, and the dire consequences that the grain has on their marriage and individual lives. We see the impact of the grain primarily from Liam’s perspective, as the episode ends with him forcefully cutting out the grain from behind his ear. At the surface level, “TEHOY” presents an unsatisfactory ending because the episode’s overt conclusion that transhuman technology ultimately seems to be unable to coexist with humans without bearing great costs on society runs contrary to the typical assumption that transhuman technology is primarily introduced to enhance people’s lives; the conclusion seems to give in easily to highlighting the problems of transhuman technology and denouncing that it is detrimental to human life. However, upon deeper analysis of how the characters interact with transhuman technology, it seems that the primary responsibility for the problems that arise from the usage of transhuman technology shifts away from the grain and towards the human users. This nuance in the text poses this question: can humans be absolved of the responsibilities of the dysfunction that surface within such a society? I find that this is important to encourage self-reflection among people about who or what bears the greatest responsibility in the event that transhuman technology bears negative consequences on society. Therefore, I argue that “TEHOY” encourages its viewers to consider how the faults that arise within a society where transhuman technology is widely used is caused by the interaction between transhuman technology and humans; while transhuman technology precipitates these problems, it is the human’s propensity to be insecure about not being all-knowing that lays the foundation for these problems. This thus has implications on how we view society.

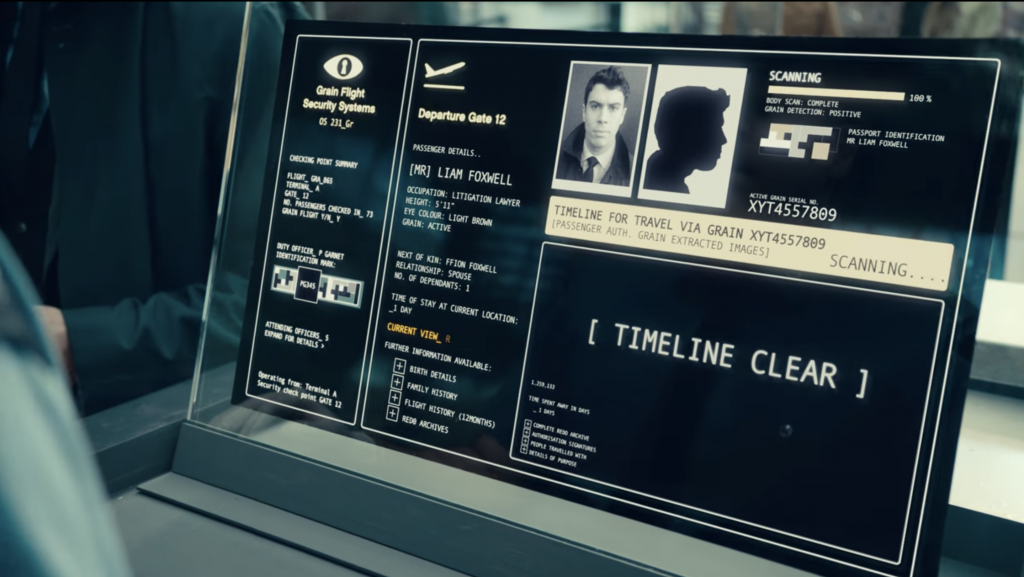

Indeed, the seemingly unsatisfactory ending of “TEHOY” that transhuman technology leads to divisions and rifts within society, despite being slated to improve human lives, is underscored by the text’s ambivalent exploration of the grain. The idea of ambivalence refers to the text’s illustration of both the beneficial and detrimental effects that the grain has on society. At the beginning of the episode, the grain is outwardly posited to be a physical modification that provides a great degree of security for its users and society at large, as the memories of the grain-users are stored for a substantially long period of time and can re-accessed whenever the users desire. The text’s introduction of transhuman technology in the form of the grain illustrates that it is originally well-intentioned because it plays a large role in maintaining state-level as well as personal-level security. We see how the grain is used to maintain airport security, as Liam is asked to replay his memories from the past 24 hours of his day, and then his past week in order to gain access to his flight. Liam goes through this protocol unquestioningly, which suggests that this system of checking for potential security threats is undoubtedly established and entrenched within society. We also get a sense that the grain is used to ensure security when Ffion checks through her daughter Jody’s grain to check on the babysitter, Gina’s, interaction with her. This behaviour follows after a joke was made at a gathering between Liam, Ffion and her friends, where Liam mentions sarcastically that the both of them had to get home to ‘rescue Jody from the paedophile babysitter’.

This explains Ffion’s underlying anxiety about her daughter’s safety and the grain thus proves to be beneficial for her to alleviate her worries. In addition to providing state-level and personal-level security, the grain also serves an important function to guard against the manipulation of the truth. The grain’s storage function fends off any possibility of artificial alteration of memories, which allows for memories to be ‘trustworthy’. This can be seen from how Colleen, who works for the grain development department, dismisses Hallam, who is a non-user of the grain technology, as she mentions that ‘half of [Hallam’s] organic memories are junk’ because without the grain, ‘false memories’ can be implanted to distort the non-user’s sense of reality. Undoubtedly, the grain does seem to serve its primary functions of upholding security both at the individual and state-level.

That being said, the beneficial element of the grain is simultaneously being undercut by the various implications that it has on the fictitious society within “TEHOY”. We would see that the prevalent usage of the grain becomes slightly problematic, due to the unsettling ethics behind how the grain is being utilised and the social implications that it has. When we take a closer look at the utilitarian purposes of the grain, it is unsettling how people’s privacy is stripped away from them for the sake of state-security, considering that having privacy is a valued norm. It is also interesting how this practice meets with little to no resistance from the characters. This suggests that the primary function of the grain to ensure individual and state-level security has become entrenched in society and the use of the grain to ensure one’s security is a norm that is widely accepted, even if it undermines the citizens’ privacy. With the grain’s pervasiveness, there are social implications in this dystopian society, in that non-users are discriminated against. Hallam experiences upfront prejudice at both a micro-level with her friends (who are patronising and dismissive towards her) as well as at a macro-level with the authorities for not possessing a grain, even in the face of danger as she still has to be screened for security purposes. The prejudice that Hallam faces, as scholar Elisa Rantoharju mentions in her master’s thesis, stems from the fact that ‘the grain has come to symbolise trust and safety’ and that ‘‘individuals appear suspicious if they have gaps in their timeline’ (43). Indeed, in a society where transhuman enhancements are used, academic Ellen McGee similarly posits in her article “Bioelectronics and Implanted Devices” that transhuman enhancements tend to cause ‘division between different classes of people’ who embrace or resist transhuman technology, which ‘[leads] to strife and even greater power and economic imbalances’ (216). Therefore, the text carefully balances the perception that the grain acts as both a boon and bane to society, which necessitates our evaluation of how the characters use transhuman technology.

While some critics find it easy to blame transhuman technology for the problems that surface in society, there is a need to examine whether these negative consequences are truly caused undisputedly by either the transhuman technology or humans. While Rantoharju’s work attributes the negative consequences from the episode to the corruptive qualities of the grain (Rantoharju 51), which has led ‘human alienation and loss of human connection’ (Rantoharju 49), McGee asserts that ‘technology itself is not evil; the uses that men devise may be’ (McGee 215). In addition, I share McGee’s view that ‘the notion that nature is somehow good and technology evil’ is ‘erroneous’. With respect to the text, it is crucial that we firstly recognise that transhuman technology is at length, only a tool for human’s usage; humans are the ones who have agency and they are the ones who have complete control over whether transhuman technology is being used productively or not. I would go further to argue that the fundamental reason why the use of transhuman technology leads to various problems within society is human’s deep-seated insecurity of not being omniscient.

In “TEHOY”, this insecurity is represented by Liam’s obsession to know the truth about his wife’s infidelity. This obsession can be seen chiefly from Liam’s compulsive psycho-analysis of key conversations that he experiences, such as his job appraisal and Ffion’s interaction with her previous partner, Jonas, at the dinner party.

We would see that by having easy access to the grain, Liam’s overuse of transhuman technology is what causes the unravelling and destruction of his interpersonal relationships, as he begins to unnecessarily scrutinise between the lines of every conversation that he has. His obsession subsequently manifests into violence against the people around him. We see this common thread of humans being insecure about not being all-knowing at the dinner party with Ffion’s friends, where tensions brew between Colleen, who is an advocate of grain technology (because of how it guards against the manipulation of truths and perpetuation of falsehoods), and Hallam, who is a non-user happy with the current state of her life. Once again, the grain gives humans agency to act as they wish to close gaps in their knowledge of the happenings around them; it is not the perpetrator of antagonism towards the characters in the text. Therefore, contrary to what the text seems to suggest at surface level (that transhuman technology is the root of social problems that arise), it is clear that humans have an equal, if not greater, responsibility for these negative consequences that arise.

As we do away with the common notion that transhuman technology is completely to blame for problems that arise within society, I argue that the text neither absolves any party—transhuman technology or humans—of its responsibility in the rifts and tensions that arise within society. Instead, it highlights how transhuman technology has an incompatible relationship with humans. In “TEHOY”, it is clear that the prevalence of the grain has already led to overreliance, as the characters’ instinct in social situations is to use the grain to attempt to connect with one another, whether they are sharing mundane details about their lives or using playbacks, “redos” to reminisce the good old days.

In fact, this incompatibility is seen from how these social situations that the characters find themselves in are plagued with awkwardness. This is particularly so for Ffion’s friends, who either find telling the dinner table unwarranted details about his sex life or judging Liam’s unsatisfactory appraisal socially acceptable or entertaining. In both instances, the recipients of the conversations are made to feel uncomfortable and the characters simply seem to be unable to connect with each other, as non-augmented humans are assumed to be able to do. Bearing in mind that humans have the tendency to be over-reliant on such forms of technology, further divisions will then occur and solidarity within society will subsequently also experience dissolution. If we were to bring this argument to its extreme, the text possibly hints at how this incompatibility, coupled with the problematic belief of how humans are usually completely exonerated of any responsibility, could lead to the drawn-out establishment of a dystopian society that is plagued by eroded social structures and disunity among people, thereby fostering an unfavourable environment for the community. This is illustrated by the problematic relationship between Liam and Ffion, as their marriage is dismantled slowly and excruciatingly as a result of their usage of the grain, which serves as a catalyst in breeding distrust and heightening insecurities between them (particularly in Liam). Liam’s suspicion would eventually lead him to confront Jonas at his home intoxicated and attack him in relentless rage.

Upon realising what he had done, Liam returns home to Ffion after the episode and as he confirms his suspicions, he proceeds to yell at Ffion abusively, thus precipitating the dissolution of their marriage as Ffion would take their child and leave the house.

The tension that the couple experience and the slow dismantling of their relationship could symbolise how this steady pervasion of transhuman technology throughout a society that can never be ready for it eventually leads to a drawn-out breakdown of society. Overall, it would be apt to ascribe characterisations to both these factors, in that while transhuman technology acts as a catalyst for the dysfunction that arises in society, humans are fundamentally responsible for the misuse of such technologies, and that both are ultimately incompatible.

In the final analysis, the seemingly unsatisfactory ending of “TEHOY”, that transhuman technology does not actually improve human lives, seems to point viewers towards a deeper reflection on the human condition due to its ambivalent presentation of the grain technology. My argument that “TEHOY” encourages viewers to reflect on the relationship between transhuman technology and humans brings about various characterisations of each—transhuman technology and humans play a catalytic and integral role respectively in causing rifts in society. When a society begins to experience degrees of dysfunction, it seems like humans’ common response is to point fingers at everyone or everything else, but themselves. In view that the fictitious society where transhuman technologies are used ubiquitously in “TEHOY” is not unimaginable, it is then crucial for us to consider how we could mitigate unprecedented ramifications to our society, in the face of rapid technological advancement. Only by reflecting on our human deficiencies can we uphold the solidarity that binds us. As we look at “TEHOY” with a renewed lens, perhaps the ending of “TEHOY” is satisfactory after all.

Works Cited

“The Entire History of You.” Black Mirror, season 1, episode 3, Channel 3, 18 Dec 2011. Netflix, www.netflix.com/watch/70264856?trackId=200257859

Rantoharju, Elisa. Fears and Fantasies about the Posthuman in Black Mirror. MS thesis. 2019.

Mcgee, Ellen M. “Bioelectronics and Implanted Devices.” Medical Enhancement and Posthumanity

The International Library of Ethics, Law and Technology, pp. 207–224., doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-8852-0_13.